- Keep Cool

- Posts

- Why we keep talking about talking

Why we keep talking about talking

What happens when a system built for consensus tries to govern a changing world

Hi there,

Today’s post is a guest post written by Jordan Breighner on how environmental agencies, regulators, and lawmakers with the best intentions can, well, get in the way of the work the world really needs to be doing. Especially over time. And not just with respect to permitting for energy generation, storage, and transmission projects in the U.S.

The newsletter in <50 words: Climate governance runs on a stability-seeking operating system from another century. Its feedback loops reward caution, repetition, and reputation. To fix it, we’ll need to redesign legitimacy around evidence, results, and the courage to act before consensus arrives.

DEEP DIVE

The world’s environmental institutions were built to slow action until consensus formed. That created stability, but it also created paralysis.

In the absence of real authority, process itself has become power — language that looks like law and fear masquerades as caution.

Legitimacy should come from outcomes, not procedure. Those with the power to act still have a choice: move, or keep waiting for permission that will never come.

How to run the world without passing a law

Pick a subject that is global, technical, and hard to visualize. The ocean will do. It is too vast to monitor and too abstract to picture, which makes it an ideal setting for the process to flourish.

Create an institution to manage it. Give it the rituals of law: conventions, protocols, amendments, and meetings. Build committees, working groups, and subcommittees. Each new acronym creates a sense of progress.

Fill the room with experts. Invite scientists, lawyers, and policy professionals who believe in the mission. They are serious, capable people who want to protect the planet. They spend their time refining definitions so that someday, when political will appears, the rules will already exist.

Invent a shared vocabulary. Use terms like urge, recommend, and express concern. They sound firm but remain flexible. Over time, this language becomes its own dialect, a shorthand that signals credibility to insiders and confusion to everyone else.

Build the culture around process, not outcomes. The institution produces documents, not results. Success is measured in consensus, not impact. The goal is to keep talking until everyone agrees that more talking is needed.

Keep the system opaque. Meetings are closed. Summaries arrive later. The structure is intentionally complex. Few people outside the room understand who is responsible for what.

Let in-group norms do the governing. The incentive is to maintain standing in the process: speak the language, attend the meetings, and be invited back next year. The real power is belonging.

Allow the documents to circulate. Reporters will quote them. NGOs will cite them. Governments will act as if they are binding. Words acquire the weight of law even when no law exists.

Then let inertia do the rest. The process will outlive its creators, continuing to regulate the world through habit and vocabulary.

The Architecture of Process

The London Protocol is one of the systems built in this mold. It is an international agreement that sits beneath another older agreement, the London Convention, created in the 1970s to stop people from dumping chemical waste into the sea. The original intent of the convention is an objectively good thing to do. The Protocol came later as an attempt to modernize that framework. Both are administered by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN-affiliated body that also manages global shipping. The IMO itself operates within the United Nations system, though it has its own councils, subcommittees, and voting rules. Acronyms on top of Acronyms.

This nesting doll of agreements is an impressive web of cooperation and a case study in how complexity becomes its own defense. Each layer is a smaller subset of nations, a narrower circle of authority, a new filter between problem and action. The structure creates the appearance of global alignment while steadily shrinking the number of people who can actually decide anything.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is a specialised agency of the UN responsible for regulating shipping. It has its headquarters in London (Shutterstock).

These institutions were built for a world that prized stability over speed. Their premise is simple: whatever enters the ocean as a result of human activities and intervention is probably harmful and must be controlled. (Ironically, CO2 entering the ocean from human activities doesn’t count). The result is a design that restrains action until consensus forms, and consensus, in a structure like this, can take decades.

The people in these rooms are not cynics. They are diligent, capable, and believe they are protecting the ocean. But the machinery they operate values process over accountability and precision over adaptability. It is an institution made of language rather than authority, a system that governs through participation rather than decision.

This week, that process will play out again in London. Delegates will gather under the IMO banner to debate what humanity may or may not do with the sea. The meetings will be thoughtful, private, and slow. At the end, there will be some sort of communiqué urging the urgent use of precaution. The ocean, meanwhile, will continue to absorb carbon. It does not care about the semantics.

The Precautionary Principle: How “Precaution” Became an Excuse for Inaction

Anyone who pays attention to the ocean agrees the ocean is in trouble - it’s hotter and more acidic than at any point in human history. The argument is about what “being careful” actually means.

The Precautionary Principle was written to make governments move faster when the planet was bleeding. Principle 15 of the 1992 Rio Declaration says:

“Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

Translated: if you already know bad things are happening, you don’t get to hide behind uncertainty. You have a duty to act.

It is not a ban on risk; it is an instruction to manage it. If the patient is bleeding, you apply pressure; you don’t wait for a meta-analysis. The moral of the principle is motion, not paralysis.

The Inversion of Precaution

Somewhere along the way, precaution became prohibition. The idea meant to stop paralysis became the justification for it: do nothing new until you can prove it is safe in advance. No field—medicine, aviation, or public health—could function under that logic, yet it has become the default language of climate caution.

Part of the reason is arithmetic, but most of it is attention. Fear captures it; proportion does not. “Potential ecological harm” sounds urgent; “carefully measured, reversible pilot” sounds like paperwork. There is no faster way to command a headline or raise money than to warn of catastrophe. Bureaucracies know this, too. It is easier to issue a statement of concern than to authorize a small experiment that might resolve it.

So the system now rewards those who amplify fear and punishes those who test solutions. Uncertainty has become a tool to stop discovery. Every new proposal lands in an environment primed for outrage, where even the smallest experiment can be framed as recklessness.

Every few years, the LC/LP community gathers behind closed doors and releases another statement reminding the world that marine carbon-removal experiments might be risky. Working groups are formed, scientists and lawyers are appointed, and papers are written about the state of the science and the law. It is a theater of caution, a ritual performance of seriousness that produces no change.

Most of the people in these rooms are doing what they believe is right. They see their work as a safeguard; a system meant to keep humanity from making irreversible mistakes. But systems built to slow down risk can be redirected by those who know how to use caution as a tool.

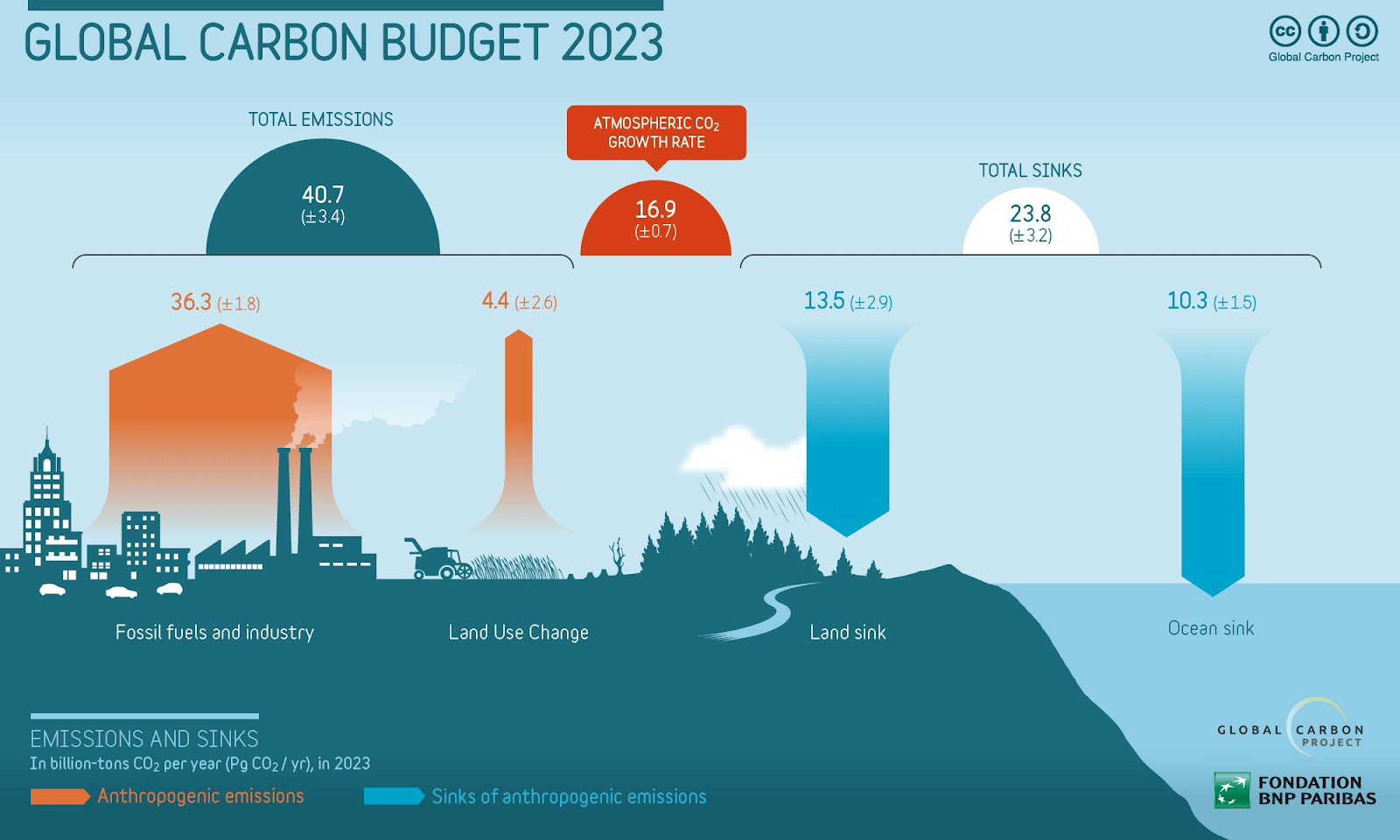

The arithmetic is simple. The ocean absorbs about ten billion tonnes of CO₂ a year. Every marine carbon-removal trial ever conducted would not register on the first decimal place of that number. But the attention economy does not deal in decimals; it deals in imagery. Place a few thousand tonnes of organic material in the ocean under a government permit, and it becomes reckless “geoengineering.” The same word used for fictional doomsday devices now applies to a single research vessel with a few nets and sensors. The scale does not matter; the story does.

This breeds asymmetrical panic. We fear the hypothetical and ignore the measurable. Ten billion tonnes of CO₂ a year dissolving into seawater is invisible and unbranded; a small, reversible experiment run by a “startup” is photogenic and therefore terrifying.

When a process is opaque and the default position is risk aversion, it takes very little to turn concern into policy. A single submission, drafted in scientific language but driven by ideology, can push an entire working group to “urge” new limits or “recommend” additional precautions. Those words are not binding, yet they echo through headlines, funding cycles, and regulatory offices as if they are law.

It is not corruption; it is incentive. Fear attracts attention, and attention shapes outcomes. For those who believe that ocean plus business equals harm, the path is simple: insert alarm into the record and let the machinery of caution do the rest.

Over time, this creates a feedback loop. The loudest hypothetical risks dominate the agenda. Each new “statement of concern” prompts another round of restraint. NGOs gain headlines, institutions reaffirm their relevance, and governments stay comfortably cautious. The science waits for permission to continue.

These institutions were built for cooperation, not competition. They were meant to create guardrails for a stable world, not to navigate an increasingly volatile one. Yet in an attention economy, that same structure turns caution into power. The process itself becomes a kind of instrument — one that can be tuned by anyone who understands its tempo. The quieter the process, the easier it is to steer.

The 2013 Amendment That Still Haunts Progress

Ask almost anyone who works in the NGO or science world but who is not steeped in the details of the IMO, and they will tell you that “marine geoengineering” is banned.

The reality is more complicated. In 2013, the Parties to the London Protocol adopted Resolution LP.4(8) — an amendment that would add new provisions on “marine geoengineering.” It was not a ban but a procedural fix: a new article, a pair of annexes, and an assessment framework that created a permitting pathway for legitimate scientific research. Then nothing happened. Only six countries have ever accepted the amendment, and two-thirds are required for it to take effect.

Legally, the amendment has about as much force as this post. It is not law. No one believes it will ever become law. Yet every year, well-intentioned delegates gather in London to urge ratification and pressure parties to “apply” its provisions as though they are binding. Over time, it has drifted into procedural folklore — cited, repeated, and enforced by reputation rather than rule. Reporters describe a “de facto ban” without noting the nuance that nothing in force actually prohibits marine geoengineering. The result is a kind of soft-law superstition: it exists everywhere in conversation and nowhere in law.

Since that day, the ocean has quietly absorbed about 128 billion tonnes of CO₂, the invisible counterpart to all that procedural caution. Every molecule has shifted the chemistry a little more, lowering pH and changing the base conditions of life. While the delegates prepare for another week of statements and concern, the math keeps moving.

By the time the meeting in London ends on Friday, the ocean will have absorbed another 150 million tonnes of CO₂. Words of caution in a joint statement or a new working group won’t change the chemistry. Process without authority. Repetition without consequence. The chemistry keeps moving.

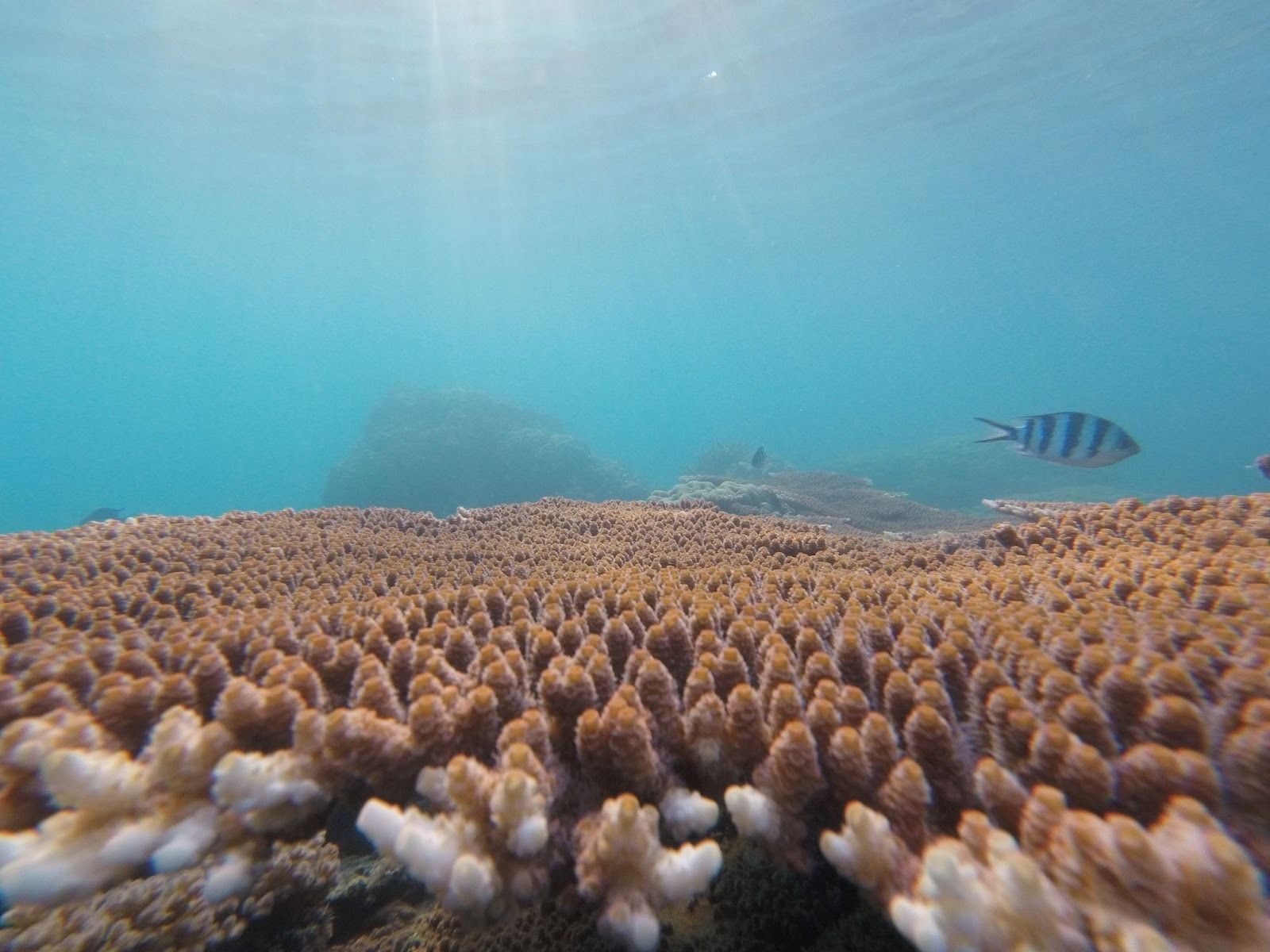

The start of bleaching on the Coral reef in the Perhentian Islands (Shutterstock).

The Real Danger

Every institution in the climate era carries a quiet contradiction. We built systems to prevent disaster by slowing ourselves down while we live in an age when disaster moves faster than our procedures. The world built for stability is colliding with a world defined by motion.

At some point, we have to decide what makes an institution legitimate. If legitimacy comes from process and caution, then the London Protocol has served its purpose: it has preserved the illusion of control. But if legitimacy comes from outcomes — from actually reducing harm and stabilizing the chemistry that sustains life — then we have to admit these systems no longer govern reality. They administer language, not change.

Everyone in this field watches everyone else for cues. Institutions wait for consensus. Companies wait for regulation. Investors follow the market.” Fear of being first has replaced fear of being wrong. It is the etiquette of paralysis disguised as caution.

That etiquette leads to the “safe” choice — the one that avoids criticism rather than the one that delivers results. But safety will not come from inaction; it will come from courage. Real security lies in backing projects that can scale and telling anyone who mistakes that courage for risk to stand aside.

Marine geoengineering is not banned. No laws prevent sovereign nations from permitting it. The prohibition exists only through repetition — in the soft power of habit and fear. It governs because we allow it to.

And this is where choice enters.

If you are an investor, a policymaker, or a buyer of carbon credits, you have more freedom than these institutions. They are designed to move slowly. You are not. When you defer to them, you surrender that freedom to a process defined by inaction — 128 billion tonnes of CO₂ absorbed by the ocean since 2013 while the paperwork gathered dust.

Use that freedom with purpose. Fund the work. Authorize the pilots. Scale the trials.

What is needed now is a rapid, transparent expansion of field research and controlled trials — biological and chemical alike — of marine geoengineering techniques that have the potential to mitigate known harms. That means permits, ships, data, and an epic amount of science.

There are risks in doing this work. But the only way to understand those risks is to do the work — carefully, publicly, and at the scale necessary to learn. This is not a call for reckless acceleration; it is a call for a world governed by evidence and outcomes, not hypotheticals. Because the outcome we are being judged on now is written in chemistry, not in policy.

The ocean is not waiting for permission. It’s not waiting for anyone or anything. The chemistry is changing with or without us. No matter what happens this week in London, the key question today, tomorrow, next week and next year, is whether those with power choose to use it.

Thoughts? Simply respond to this email and I’ll be sure to pass them along to Jordan.

— Nick

Reply