- Keep Cool

- Posts

- Super pollutants 101

Super pollutants 101

A guide to the pollutants warming the planet fastest

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH

Hi there,

Since super pollutants are en vogue now (rightfully so), Lauren Singer and I thought it'd be good to pen a primer on all the non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gasses, mitigation of all of which is essential if not higher-leverage in the short-term, especially, to stave off the worst impacts of climate change. Read on, hope it's useful, and be sure to subscribe to our newsletter, superpollute, as well.

Fast, accurate, affordable CleanTech recruiting with ErthSearch

Traditional search firms are slow, have limited access to climate talent, and have bloated costs. It’s time you worked with a search firm that matches the energy of your CleanTech startup. ErthSearch is that firm.

Take ChargeScape. In 6 months, ErthSearch helped them hire an 8-person leadership team, saving them ~$380k in recruiting fees. They have 80+ placements, the largest CleanTech network, and unparalleled service to ensure no candidate is left behind.

If you’re ready to grow your team and want a partner who will move at the speed and accuracy that you need, at prices you can afford, reach out to ErthSearch today to get started. Book a call or email them directly → [email protected]

DEEP DIVE

In this edition, inspired by the recent release of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition’s (CCAC) Super Pollutant Factsheet, we’ve created a super pollutant 101.

Building on top of CCAC’s excellent factsheet and report, this additional resource breaks down all major super pollutants with a distillation of what they are, where they come from, insights into existing and future mitigation strategies, and groups already working towards mitigation.

Whether you’re a super pollutant professional or new to the conversation, there’s something in it for everyone.

Let’s start with the fundamentals.

What is a super pollutant?

The CCAC, in its Super Pollutant Factsheet, defines super pollutants as follows:

“Super pollutants are a group of atmospheric pollutants that have greater impacts on warming than carbon dioxide per ton, and can have other environmental and human health effects.” *

The super pollutants are:

Methane

Tropospheric ozone

Tropospheric ozone precursors (e.g., carbon monoxide, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs))

Fluorinated gases (F-gases, such as sulfur hexafluoride, and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs))

Nitrous oxide

Black carbon

Note that this graphic, also courtesy of the CCAC, combines all F-gases (HFC and otherwise) and subsumes tropospheric ozone with methane

Why are super pollutants important?

Super pollutants are responsible for half of global warming to date, and reducing their emission translates to reduced global warming faster than reducing carbon dioxide emissions

Reducing their emission could help avoid 1° C of warming by 2100

Reducing their emission offers many other public health and economic co-benefits, like decreasing air pollution

If we combine the warming impact of all seven super pollutants together, the category has driven half of the global warming the world has experienced since the Industrial Revolution. Because, definitionally, super pollutants are, pound for pound and molecule for molecule, stronger climate forcers than carbon dioxide is, mitigation of them is (again, pound for pound), a faster way to reduce near-term warming.

Especially as the world enters a climactic “overshoot” scenario—in which, despite progress on decarbonization efforts, estimates of future warming to 2100 still range from 2.4° C to 2.9° C, levers that drive near-term warming reductions are critical, lest we risk triggering tipping points in critical climate systems. Because those risks are rising non-linearly as every incremental fraction of a degree of warming does. For one example, recently, Iceland became the first country toZ designate a potential tipping point in a critical climate system as a national security concern when it formally presented the potential destabilization of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) current system to the National Security Council.

Reducing super pollutant emissions alongside carbon dioxide emissions could avoid up to three times more warming by mid-century than decarbonization alone (as per the CCAC factsheet). The scale of potential warming mitigation that this translates to by virtue of cutting super pollutant emissions is an additional degree of avoided warming by 2100. As the narrative surrounding destabilization risk and tipping points in Earth’s climate system strengthens in parallel to the narrative surrounding super pollutants, we should effectively pair the two and state clearly that:

Super pollutant mitigation is the best way to reduce near-term climate risks.

Other options to reduce near-term warming are not nearly as well-studied, economical, or even technically feasible. Plus, super pollutant mitigation offers many additional and immediate public health co-benefits. Many super pollutants are air pollutants, contribute to the formation of air pollutants, or are co-emitted with air pollutants, all of which harm human health and damage crops. As one example, recent research estimates that tropospheric ozone suppresses wheat yields by more than 10% in India. By mid-century, reducing super pollutants could prevent millions of premature deaths annually and save tens of millions of tonnes of crops annually, by improving air quality through reductions in both super pollutants and their co-emissions. [3]

Let’s now explore each super pollutant in greater detail, ordered in terms of its percent contribution towards global warming from largest to smallest.

[3] Aggregated from data in CCAC Integrated Assessment of Black Carbon and Tropospheric Ozone (2011); CCAC Global Methane Assessment (2021);

CCAC Global Nitrous Oxide Assessment (2024).

Image also courtesy of the CCAC

Now let’s break them down, one by one:

Methane (CH4)

What it is: Methane is both a greenhouse gas and an energy-dense fossil fuel (it is the main component of natural gas). It’s composed of four hydrogen molecules and one carbon molecule. As a greenhouse gas, it traps heat much more readily than carbon dioxide, though its atmospheric life is also much shorter than carbon dioxide’s (which is 300+ years). To date, it is the second-largest contributor to post-industrial global warming.

% contribution to present day global warming: ~30%

Average atmospheric lifetime: ~12 years

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: ~80x

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: ~30x

Emissions sources: The predominant emissions sources of methane are best bifurcated first into anthropogenic (human-caused) sources making up ~60% of all emissions, and natural releases making up ~40% of all emissions from ecosystems like wetlands, thawing permafrost, and the ocean. In the human-caused category, the largest contributing sources include ruminant livestock (cows, goats, and sheep), the oil and gas industry, landfills, and other agricultural and waste sources.

Image sourced with permission from Shutterstock

Commercializable mitigation efforts: There are many readily commercial mitigation options for methane emissions, which vary across emissions sources. Reducing consumption of meat, milk, and cheese sourced from ruminants would, for instance, offer a direct methane mitigation impact by reducing cattle, goat, and sheep herd sizes globally. To date, the largest sources of successful methane mitigation efforts have come from remediating oil and gas infrastructure that leaks or vents methane, reducing flaring of natural gas on oilfields and/or making flares more efficient, and building infrastructure to capture gas from landfills, dairy barns, and other concentrated emissions sources.

Future mitigation efforts: In the future, there’s significant promise that solutions like feed additives and vaccines might scalably support methane mitigation efforts in agriculture, while even more novel scientific and technological advances, such as research into direct atmospheric methane removal (destruction via accelerated oxidization) are advancing as well.

Tropospheric Ozone

What it is: Ozone is a molecule composed of three oxygen atoms. Tropospheric ozone, often referred to as ground-level ozone, is a secondary air pollutant and a potent greenhouse gas that efficiently absorbs infrared radiation from the Earth’s surface, thereby trapping heat in the lower atmosphere. Tropospheric ozone is formed by chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (including nitrous oxide, specifically), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the presence of sunlight. Unlike stratospheric ozone (i.e., the ozone layer), which protects against ultraviolet radiation, tropospheric ozone poses both climate and health risks.

% contribution to present day global warming: ~10%-15% of today’s warming combining tropospheric ozone, carbon monoxide and NMVOC emissions together.

Average atmospheric lifetime: Weeks to months

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: N/A*

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: N/A*

*Highly contingent on altitude and location; can range up to 2,000x more powerful GWP than CO2

Emissions sources: Tropospheric ozone is not emitted directly. It forms when precursor chemicals—nitrogen oxides (for instance, nitrous oxide emissions from vehicles or power plants) and VOCs—react under sunlight. The largest sources of ozone precursors, and therefore, tropospheric ozone formation itself, are fuel combustion in urban environments, fossil fuel combustion in general, and natural releases of VOCs and nitrogen oxides from other fires.

Commercializable mitigation efforts: Mitigation efforts for tropospheric ozone run through the mitigation of methane, nitrogen oxide, and volatile organic compound emissions and pollution. As we’ll explore with respect to those super pollutants’ subsections, these efforts primarily focus on transitioning away from fossil fuels in general, upgraded vehicle emission controls, air-quality standards, and improved combustion efficiency in engines and industrial settings.

Future mitigation efforts: See future innovation sections for tropospheric ozone precursors, especially methane, nitrous oxide, and VOCs.

Carbon monoxide (CO)

What it is: Carbon monoxide is, like other super pollutants, a colorless, odorless gas. Containing a lone carbon and oxygen molecule, it is predominantly the product of incomplete combustion of carboniferous fuels like gas or wood and charcoal. It’s also poisonous, hence why there’s a carbon monoxide monitor in many of the rooms you likely spend time in. Carbon monoxide is not a direct greenhouse gas insofar as it does not directly drive additional global warming alone. But it indirectly increases warming by reacting with hydroxyl radicals (OH) that otherwise oxidize methane into carbon dioxide, normally removing methane and its stronger warming potential from the atmosphere.

% contribution to present day global warming: ~10%-15% of today’s warming combining tropospheric ozone, carbon monoxide and NMVOC emissions together

Average atmospheric lifetime: 1-2 months in the troposphere

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: ~6x

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: ~2x

Emissions sources: Carbon monoxide emissions are predominantly a product of incomplete fossil fuel combustion, especially in engines in vehicles as well as in industrial settings and coal power plants. Wildfires and biomass burning (really, most types of fires), can also produce them.

Commercializable mitigation efforts: Carbon monoxide mitigation efforts ultimately hinge and will progress in lock-step largely with decarbonization and an energy transition away from fossil fuels, the combustion of which is this super pollutant’s primary emissions source. That said, targeted interventions, such as improving combustion efficiency in engines and strengthening vehicle and industrial emission controls, have historically driven massive amounts of progress, particularly in developed economies. As introduced with respect to nitrous oxide emissions from tailpipes, most cars today, thanks to catalytic converters and other controls and interventions, emit less than 1% as carbon monoxide compared to cars that our grandparents drove. The same is true for VOC emissions from cars. In developing economies, in addition to switching to cleaner fuels and reducing fossil fuel use, reducing practices that are harmful for many reasons, such as open biomass burning (common in large rice planting regions), are also high-leverage.

Future mitigation efforts: Significant innovation and scientific research isn’t needed, at least not in addition to the ongoing scope, scale, and required speed of the energy transition at large.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs)

What it is: Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are their own larger class of carbon-based chemical compounds that evaporate (volatilize) easily. Specifically, they feature a high vapor pressure (which is what allows them to easily evaporate at room temperature). Formaldehyde and benzene are two recognizable examples. Some VOCs are direct greenhouse gases, while others aren’t. On the whole, similar to carbon monoxide, VOCs drive more warming indirectly than directly, as, like carbon monoxide, they react with other pollutants in the atmosphere to form ground-level ozone, a more potent greenhouse gas than VOCs are directly.

% contribution to present day global warming: ~10% of today’s warming combining tropospheric ozone, carbon monoxide and NMVOC emissions together.

Average atmospheric lifetime: Minutes to years (contingent on source)

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: ~2x

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: ~0.4x

Emissions sources: VOCs are emitted by a wide range of both natural and anthropogenic sources. The natural sources range from plants—like common indoor plants such as the Snake Plant and Peace Lily, which, surprisingly, actively emit VOCs—to volcanos. Anthropogenic sources range from combustion of fossil fuels (and things like cigarettes) to everyday household products like paints, cleaners, and cosmetics. The lion’s share of anthropogenic VOC emissions stem from fossil fuel and industrial applications, including but not limited to vehicle exhaust, oil extraction, and industrial solvents, and water treatment by-products. Cooking fuels like biomass and charcoal, and liquefied petroleum also release VOCs.

Commercializable mitigation efforts: In addition to phasing out fossil fuel use and continuing to advance emissions control standards in engines and in industrial applications, providing access to cleaner cooking fuels and switching to induction (electric stove) tops are all readily commercializable strategies to mitigate VOC emissions. Cleaner cooking fuels in particular are a worthwhile focus area; research from NOAA estimates that the amount of ozone production from VOCs generated by cooking food in the Los Angeles basin (not a developing country, mind you) is roughly equal to the amount of ozone produced by VOCs from motor vehicles.

As with carbon monoxide, VOC emissions from newer vehicles have decreased significantly over time thanks to tighter regulations and tech advancements like catalytic converters, but VOC emissions holistically won’t be under control until EVs are the norm and other sources, like cooking, receive significantly more investment and attention, especially in developing countries. More on those efforts will be explored in the Black carbon section.

Future mitigation efforts: Beyond cleaner cooking fuels and continued progress transitioning away from fossil fuels and ensuring cleaner combustion of them, future mitigation efforts for VOCs could include R&D and innovation into low-VOC paints, solvents, and other household products that traditionally emit them. Lower-VOC-intensity fuels can also continuously be advanced, but switching from fuels to electricity in general is desirable.

F-Gases

What it is: F-gases are a group of synthetic, fluorine-containing greenhouse gases that include perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF₃) used for niche industrial applications like electrical insulation, high-voltage switchgear, semiconductor manufacturing, specialty refrigeration, and some fire suppression systems. They are also extremely powerful greenhouse gases and unique among most super pollutants in that they can persist in the atmosphere for hundreds to tens of thousands of years

% contribution to present day global warming: 5% of today’s warming

Atmospheric lifetime: years to decades, more details below

HFCs: up to 270 years

PFCs: 2,600–50,000 years

NF3: 740 years

SF6: 3,200 years

Average atmospheric lifetime: 1,000 to 50,000 years depending on the gas

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: Up to 23,500x (for SF₆, the most powerful greenhouse gas known to man)

Emissions sources: F-gases are primarily emitted via leakage or improper handling during certain industrial processes. SF₆ is used as an insulating gas in high-voltage electrical equipment and during magnesium production. Faults in these systems can lead to emissions. Perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) can be released during aluminum smelting and semiconductor manufacturing. NF₃ is mainly linked to electronics manufacturing, like solar cell manufacturing, during which it can also leak.

Commercializable mitigation efforts: Cutting F-gas emissions hinges on developing leak-tight systems, boosting maintenance, recovering and recycling the gases, and deploying technological substitutes such that their use and production in general is rendered obsolete. For SF₆, alternatives like vacuum or CO₂-based switchgear are gaining commercial adoption, while stricter handling and reclamation strategies are increasingly mandated for PFCs and NF₃ in electronics and metallurgy.

Refrigerant gasses used for air conditioners; image sourced with permissions from Shutterstock

Future mitigation efforts: Next-generation cooling and electrical equipment are being engineered to be F-gas-free, and technological innovation in byproduct capture, recycling, and destruction is expanding. International treaties (like the Kyoto Protocol, more on which follows with respect to HFCs) specify reduction obligations, and research into benign alternatives is a near-term industrial priority given F-gases’ permanent, cumulative warming impact.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

What it is: Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are a category of synthetic (all human-made) greenhouse gasses used primarily as refrigerants and solvents in the production of insulating foams and packaging materials. HFCs were originally created to replace chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), which were the primary culprits in ozone depletion before the Montreal Protocol, ratified in 1987, to phase out the use of CFCs to protect the ozone layer. There are many HFCs, all of which carry different characteristics; for instance, HFC-23 has a global warming potential (GWP) that is 14,800 times higher than carbon dioxide over 100 years, emissions of it are still increasing globally. HFC-134a, meanwhile, is increasingly the subject of stricter regulation in jurisdictions like the E.U.

% contribution to present day global warming: 5% of today’s warming including all fluorinated-gases

Average atmospheric lifetime: ~15 years

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: Up to 3,790x

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: Up to ~1,400x

Emissions sources: HFC emissions primarily come from the use, leakage, and disposal of equipment in refrigeration, air conditioning, foam blowing, and some specialty industrial applications. Growth in global cooling demand directly drives HFC release, especially in developing countries with rising demand for and access to air conditioning. 20% of all HFC emissions stem from China, where many HFCs are produced.

Commercializable mitigation efforts: The Montreal Protocol, while focused on phasing out CFCs, not HFCs, remains a highly instructive example of globally coordinated and highly successful climate action, as some estimates suggest that by saving the ozone layer and for other climate system dynamics, reducing CFC emissions will have staved off an additional 2.5° C of warming by the end of this century. An amendment to the Montreal Protocol, namely the Kigali Amendment, ratified in 2016, now aims to accelerate a similar phasedown in HFCs, considering their potency as a greenhouse gas. Successful, wholesale mitigation will also depend on the work of companies like Tradewater that actively seek out and decommission or destroy HFCs and produce carbon credits as part of their business model.

Future mitigation efforts: R&D and innovation in refrigerants is critical to iteratively create less environmentally harmful synthetic gasses. HFCs were already a purposive evolution from CFCs; today, alternative refrigerants like Hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) are increasingly emphasized, as well as different systems entirely, such as carbon dioxide cascade systems used in large refrigeration systems for supermarkets. What makes HFCs useful is their thermodynamic properties, which allow them to efficiently absorb and release heat; they’re, simply put, highly efficient. But plenty of alternative cooling systems exist and can be purpose-built for different applications.

Nitrous Oxide (N2O)

What it is: Nitrous oxide, consists of one nitrogen atom and two oxygen atoms. Also used as “laughing gas,” it is colorless and non-flammable. Like methane and carbon dioxide, it is a naturally occurring component of the atmosphere, but human activities, especially agriculture, have increased its concentration to the highest levels in modern history in recent centuries. It is also an even more potent greenhouse gas than methane and is also the largest current contributor to ozone layer depletion (CFCs used to be until their use was phased out).

% contribution to present day global warming: 5% of today’s warming

Average atmospheric lifetime: ~121 years

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: ~270x

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: ~270x

Emissions sources: While natural sources, such as oceans and forests, do emit nitrous oxide, these emissions have remained relatively stable over recent centuries. Excess nitrous oxide emissions are human-caused and largely stem from agriculture and soil management (which represent 65% of human-caused emissions). Specifically, the majority of human-caused nitrous oxide emissions are a result of the application (and overapplication) of nitrogen fertilizers, which ‘feeds’ microbes that produce nitrous oxide. Similarly, nitrogen in manure and urine from livestock also often breaks down into nitrous oxide. Beyond agricultural sources, combusting fossil fuels produces nitrous oxide alongside other greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide.

Commercializable mitigation efforts: Mitigation strategies for nitrous oxide emissions are readily scalable and commercializable. Catalytic converters, as one example, are a technology designed to mitigate nitrous oxide emissions at their source, namely, in this case, car tailpipes. Similarly, with respect to the primary source of anthropogenic nitrous oxide emissions, namely agriculture, precise application of fertilizer could offer significant mitigation benefits. Simplifying using less fertilizer is not a particularly tenable suggestion, given that 40%+ of humanity is estimated to depend on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers for its food supply. Further, overapplying fertilizers is far less costly to farmers than underapplying is. Still, the IATP estimates that only ~20-30% of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers applied are converted into food. The rest pollutes ecosystems like waterways and the environment. Empowering farmers with better data and tools for precision fertilizer application (and better crops and fertilizers) is the key thrust of mitigation efforts in agricultural systems that otherwise produce nitrous oxide emissions.

Future mitigation efforts: Continued R&D and innovation efforts towards all areas listed above: Phasing out fossil fuel combustion, solving precision fertilization challenges (most critically), and eliminating food waste in general, will all help further reduce emissions.

Black Carbon

What it is: Black carbon is fine particulate matter produced by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, and biomass like wood. Since black carbon is not a gas, it is also not a greenhouse gas. But black carbon particles are a primary component of soot and, given their color, readily absorb sunlight. Hence, black carbon drives warming by reducing natural albedo effects elsewhere; for example, when black carbon in soot settles on snow, it reduces its reflectivity, shifting global radiative forcing dynamics. Soot and black carbon from wildfires can also travel thousands of miles; black carbon from Canadian wildfires has been found as far away as in Antarctica. Black carbon should not be confused with carbon black; while also a product of incomplete hydrocarbon combustion, carbon black is a versatile material used in industry.

% contribution to present day global warming: 5% of today’s warming

Average atmospheric lifetime: 4-12 days

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 20 year period: ~660

Warming impact compared to CO2per unit of mass over a 100 year period: ~270

Emissions sources: Black carbon emissions are predominantly released in fossil-fuel combustion, as well as burning of wood and other fuels, especially for cooking, and burning waste. Similar to other super pollutants, black carbon emissions can also stem from natural combustion sources like wildfires and intentional burning of excess biomass. Within fossil fuel combustion, diesel engines are particularly pernicious black carbon emitters.

Southern Icelandic Sólheimajökull glacier covered in volcanic soot (Shutterstock)

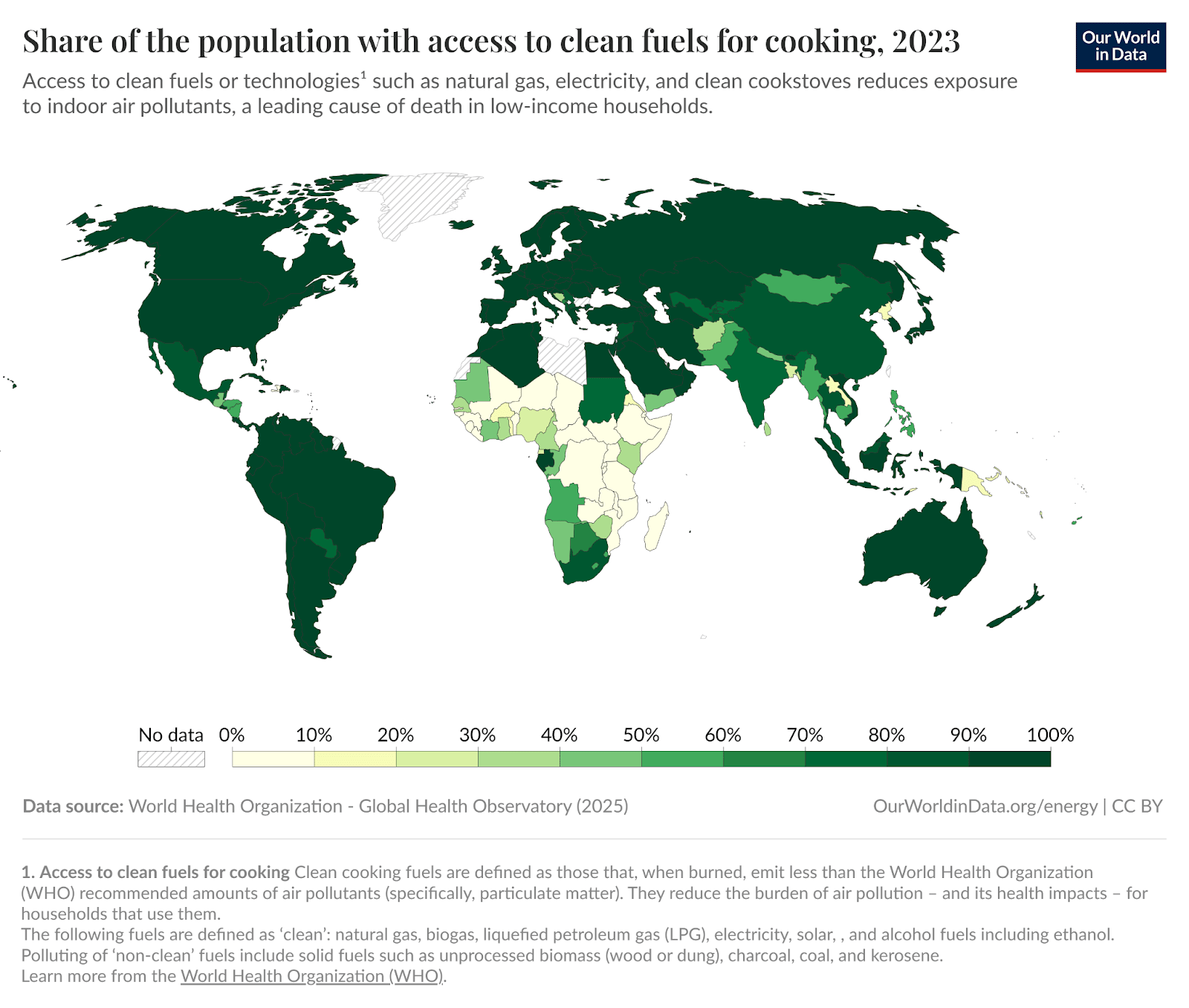

Commercializable mitigation efforts: One example of mitigation efforts for black carbon, which would also offer significant co-benefits for decarbonization, other super pollutant mitigation, and human health and economic development at large, entails ensuring access in developing countries to clean cooking fuels. Thirty percent of the global population doesn’t have reliable access to clean cooking fuels (at least didn’t, as of 2021). These people burn dung or charcoal to make fires to cook, and they often do so inside, which is terrible for their health. Organizations focused on providing access to clean cooking fuels include the Clean Cooking Alliance and the Clean Cooking Fund.

Future mitigation efforts: Significant development of additional mitigation strategies isn’t particularly essential here beyond phasing out fossil fuel combustion, preventing biomass burning in agriculture, and commercializing cleaner cooking fuels for all.

Super pollutants pack extremely powerful short-term warming impacts, far stronger than CO₂. Because they break down quickly, cutting them can noticeably slow global warming within years while also reducing extreme weather, protecting crops, and improving air quality. Reducing super pollutants is the fastest, most cost-effective way to cool the planet and deliver immediate health and climate benefits. It’s the best way to buy time for decarbonization efforts to materialize. As you can imagine from the name of our newsletter, we consider advocating for and advancing this strategy one of the most important uses of our times (and yours as well).

Thank you for reading the 29th edition of superpollute. If you don’t already, subscribe and forward this to a friend, family member, or colleague who might be interested.

— Lauren & Nick

Reply