- Keep Cool

- Posts

- Nothing for granted. Thanks for everything.

Nothing for granted. Thanks for everything.

On the passing of a dear friend, tipping points, and systemic risk

Hi there,

Happy Thanksgiving to all who celebrate. On this Thanksgiving eve, and in this reflective time of year, I’ve penned some more somber, ideally useful, words. I’ll start with reflections on the recent passing of a dear friend as grounding context for more on the climate-focused content I’m spending most of my time thinking about these days.

The newsletter in 50 words: Many climate systems have already absorbed far more than their fair share of climate change-driven stress. As resilient as they are, we don’t and cannot know definitively how much more they can take. And the amount of risk we can acquiesce to regarding their potential “tipping” or breakdown is zero.

Humanity is one system comprised of many

About ten days ago, I found out that a dear friend of mine had passed away. I won’t go into the details, but it was, unfortunately, not a surprise. I’d feared as much for some time.

I found out while I was driving home from another friend’s wedding in Santa Barbara. It was a lovely wedding. Cast in relief against the weekend I had just enjoyed—full of wonderful time spent celebrating friends, their love, and hanging with other friends, many of whom I don’t see much, and all of whom are, in their own ways, growing into happy, complete human beings—the news reminded me of something I’ve thought about more in recent the years.

Specifically, the quasi-evolutionary biology idea is that if one considers the human species as both comprised of billions of individuals and as a collective whole (“the body is not one member, but many”), it makes sense that deep despair—of which there is, unfortunately, so much—isn’t distributed evenly throughout the entire organism. Rather, much of it often concentrates in a few. As in our body, we have specific organs tasked with filtering out and processing toxins. It wouldn’t make sense for all our own individual organisms to be engaged in that work in an equally distributed fashion (it’s “better” to partition it). Similarly, it doesn’t make sense for our collective human organism to do so either.

This may land as largely “woo,” and I don’t expect it to make sense to everyone. Further, it is of course not my intention to detract in any way from the pain I know that everyone traverses. But I do believe some people on this Earth take on inordinate amounts of it—much of it fundamentally disconnected from immediate circumstances or specific events—for the rest of us. And I do believe that this distributive function, and the deep work of the “saintly sponges”—many of whom take on their task quietly and often thanklessly—exists in service of most of our great fortune. It is the rest of our lot to be so lucky.

Earth’s climate is one system comprised of many

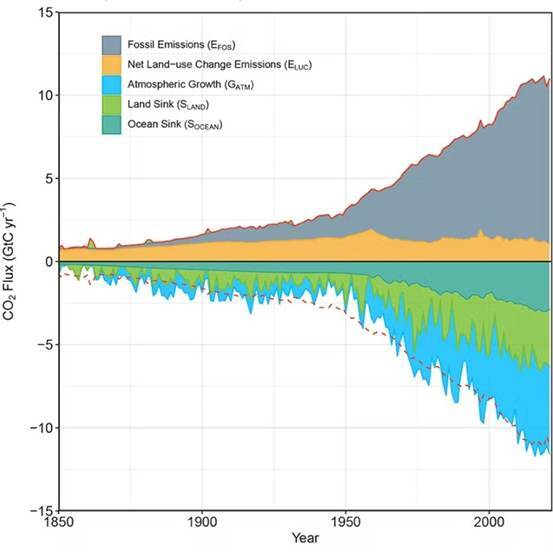

Insofar as we can characterize the human species as both comprised of individuals and, ultimately, as one collective, echoes of the analogies drawn above are even more irrefutably true at the scale of Earth’s climate system. There are countless buffers built into the complex, interwoven ways in which the Earth, inordinately elegantly, manages stressors and changes to the comprehensive system (such as escalating atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations). There are countless counterbalancing forces that function in service of overall system stability. That Earth’s oceans have absorbed ~30% of excess carbon dioxide emissions since the Industrial Revolution is but one example.

But these bulwarks can’t all handle everything thrown at them in perpetuity. As I noted last week:

“Earlier this year, scientists monitoring forests in Australia released research suggesting that those forests may have stopped acting as net absorbers of carbon.”

Which tips my hand a bit insofar as where I’m going with this.

Tipping points (are to be taken the opposite of lightly)

The term “tipping points” has become more pervasive in climate science communications of late. A recent piece in NPR did a good job offering some tipping point 101 as follows:

“When the planet heats up beyond 1.5 degrees, the impacts don't get just slightly worse. Scientists warn that massive, self-reinforcing changes could be set off, having devastating impacts around the world.

Such changes are sometimes called climate tipping points, although they're not as abrupt as that term would suggest. Most will unfold over the course of decades. Some could take centuries. Some may be partially reversible. But they all have enormous and lasting implications for humans, plants and animals on Earth.

And every tenth of a degree of warming makes these tipping points more likely, according to a new report from 160 international climate researchers.”

Practically, some key tipping points (also referenced in the NPR article) include:

The loss of coral reef ecosystems globally (which may have already crossed a tipping point from which holistic recovery isn’t possible).

Collapse of ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica (which contain about two-thirds of the freshwater on Earth).

Thawing permafrost and other frozen soils globally (which currently sequester 1.4 trillion in carbon, the release of [even some of] which could supercharge warming).

Methane percolating up in an otherwise frozen lake (Shutterstock)

A lot of the increased attention to tipping points in Earth’s climate systems has (rightfully) been catalyzed by growing recognition from the broader climate science community that the Earth is already in an “overshoot” scenario; one in which we are clearly, collectively, hurtling past 1.5° C and even 2° C warming thresholds. Despite progress on decarbonization efforts, estimates of future warming out to 2100 still range from 2.4° C to 2.9° C.

As I’ve often written, the central problem with this overshoot scenario is not the warming, climate change, and what we know it will have wrought out to 2100 alone. There are trillion-dollar loss and damage estimates for that, as I referenced in a piece I syndicated in these pages last week:

“Moody’s estimates that in 2050, the global economic impact of physical risk may reach $41.4 trillion, or a 14.5% loss in [GDP].”

What I’m ultimately more concerned about are the things we don’t know. I think a lot of what underlies the hoopla that accompanied Bill Gates’ new memo wasn’t so much the arguments he laid out themselves or what he advocated for, which I’d summarize as largely an exercise in opening the aperture to say “We need to manage and mitigate climate change holistically, and tackle countless other global health challenges simultaneously.”

I’m all for that. Nor is it really all that dissimilar from what Gates has always said. But I think the tenor and timbre of the memo, and especially the timing of the release, were overly cavalier in suggesting, even implicitly, that we know for sure that climate change will not be catastrophic. I am not a climate change catastrophist. I do not think there’s much room in climate comms for that, insofar as it is predominantly an antithesis to action and agency.

That said, more often these days, I find myself asking “How can we be sure?”

The simple truth is that we can’t be. Earth’s climate system is so complex as to be tautologically unknowable and impossible to model in full. That is not to say we aren’t constantly learning more about it, nor that we don’t know more about it than ever. But, in fact, the more we learn, the more we appreciate that there are certainly non-zero risks that the warming trajectories we’re heading down could stress certain critical climate systems so much so as to render their irrevocable tipping towards collapse.

Scientific understanding of the rising risks of destabilization in climate systems, such as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), has advanced considerably in recent years. When we view all the climate systems at risk of “tipping” collectively, the comprehensive risk is best characterized as wholly systemic: Continued global warming breeds non-linear instability and risks triggering cascading breakdowns in climate systems, amplified by reinforcing feedback loops.

As long as the risks of climate systems “tipping” remain meaningfully non-zero, and the proper comprehensive risk assessment remains “systemic,” we should (must, really) treat our near-term warming trajectories as seriously, if not more seriously, than long-term ones. Again, I am writing this from a place of no small heartbreak in light of a highly appreciable corollary from my personal life to anchor it in. There are limits past which extremely resilient people and extremely resilient systems can’t be pushed. You won’t ever know exactly where the real tipping point is. But you will know when it’s been passed.

There are limits past which extremely resilient people and extremely resilient systems can’t be pushed. You won’t ever know exactly where the real tipping point is. But you will know when it’s been passed.

The consequences of insufficient intervention are not measured in dollars. They’re immesurable, really. Every chance we have to make tipping point risks, whether for people or planet, materially closer to zero, strikes me as some of the most important work I could hope to help with for the foreseeable future.

Seeds for the necessary sea change

Sadly, unlike the common knowledge that has coalesced surrounding the warming overshoot scenario the Earth is now in, one area of climate science in which there isn’t even a remote semblance of agreement is in how to appropriately intervene to reduce the risk of crossing tipping points in critical climate systems. Many climate scientists and practitioners are stuck in a misguided perspective that mitigating greenhouse gas emissions as fast as possible and removing excess emissions from the atmosphere via carbon removal is most important and is all that we should be doing.

The NPR piece, which outlines tipping point risks well for a general audience, made a similar mistake:

“However, all is not lost. If countries can cut overall greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2035, scientists say the planet would quickly return to lower levels of warming.”

While mitigating greenhouse gas emissions is, of course, essential, the above statement is simultaneously wrong and impossible. The world will not halve its greenhouse gas emissions by 2035. Full stop. The world hasn’t even peaked its greenhouse gas emissions. I will happily bet you $100,000 to $100 on this; if global GHG emissions do indeed halve in ten years, you get $100,000. If they don’t, I get one half-decent dinner in New York City.

Secondly, carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for 300+ years. Halving emissions (mind you, we’re not even discussing reducing them to zero) will do little to “return to lower levels of warming” quickly. The real toolkit to reduce near-term warming is:

Super pollutant mitigation: Reducing emissions of super polluting greenhouse gasses, many of which have a dramatically shorter atmospheric life and all of which have much higher warming factors than carbon dioxide, drives much faster warming reductions (or, at minimum, more near-term avoidance of additional warming) than carbon dioxide mitigation alone does. I write all about that all the time over here all the time.

Near-term strategies to mask additional warming: Whether it’s stratospheric aerosol injection, enhancing surface albedo and reflectivity in any number of places, or any number of other strategies, there are plenty of ways to temporarily blot out some sun, though I’m under no illusion that the requisite scientific and technical capacity, let alone geopolitical consensus, to deploy these solutions at large-scales exists today. We should get there, ASAP, though.

Beyond that, while pulling the first and perhaps some of the second above levers to slow near-term warming, there’s a whole slew of other “prevention and intervention” mechanisms that could help slow and even stave off destabilization in climate systems. This category deserves more room than I have for it here today, and really deserves a library of high-visibility literature, which I’m excited to begin building with organizations like ARC. There are, for instance, teams working on restabilizing ice sheets otherwise at risk of collapsing (see also the Arctic Climate Emergency Response Initiative).

We’re also seeing increasing research into and actual motion in inland sea reflooding efforts to combat sea level rise (and to deliver countless other co-benefits). Israel is actively refilling the Sea of Galilee. There’s exciting research going into potential cooling technologies to protect coral reefs (among many potential applications). I could list dozens more solutions here and will get to them in time.

The point of the paragraphs above is both introductory and, ideally, to excite, energize, and counter the continued carbon-dioxide-stuff-only myopia. We need not (really cannot) view a cohesive, global, climate change mitigation and management strategy as one comprised of carbon dioxide-focused solutions alone. Nor of greenhouse gas mitigation solutions alone, either (as much as I deem super pollutant-focused work extremely necessary and extremely high-leverage at this point). We can and should be researching—and allocating significant funding towards—physical prevention and intervention strategies designed to shore up climate system stability and reduce the risk of crossing climate system tipping points. If and where there are questions of moral hazard and geopolitical and governance-focused concerns about doing so, great! We should eagerly engage with them and actively encourage scientists and policymakers (and maybe even philosophers!) to pursue them.

Fortunately, now is as good a time as any to be making these arguments. Earlier this month, Iceland became the first country to designate a potential tipping point in a climate system as a national security threat. Specifically, it presented the destabilization of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) current system to the National Security Council. While a slowdown, let alone a collapse of the AMOC would be disastrous for society, ideally, this moment of recognition marks a sea change in the climate discourse.

The Overton Window is shifting here. And I’ll continue to push it as much as I can.

It’s perniciously, perilously easy to assume that tipping points, whether in the lives of your people or at the scale of Earth’s climate systems, are not at imminent risk. Over the past year or so, I’ve been entirely, earth-shatteringly disabused of any and all of the quotidian, comforting ideas that so often come to mind to quell the near-term anxieties.

“That’s a few decades off.”

“We’re not so sure how high the risk of that happening is, anyway.”

“It’ll work itself out, one way or another.”

“I’ll deal with that tomorrow.”

Nope. Sorry.

What am I thankful for this Thanksgiving? As always, countless things. As it pertains to the remit of what I write about in these pages, it’s that countless people and organizations are increasingly leaning into, rather than away from, researching how to conscientiously, directly intervene in the highest-sensitivity, most at-risk climate systems. Which, together, underpin the functioning of our planet.

And, otherwise, that I had the time with my friend that I did. And for all that she alchemically metabolized for the rest of us. So that we may live.

Go with grace,

— Nick

Reply