- Keep Cool

- Posts

- Inkjet sprinkling

Inkjet sprinkling

Making irrigation considerably more efficient to save water

Editor’s note: The original version of this post lived here pre-migration.

Before we get into it, here’s one of my favorite Zen koans:

A Zen master named Gisan asked a young student to bring him a pail of water to cool his bath.

The student brought the water and, after cooling the bath, threw on to the ground the little that was left over.

“You dunce!” the master scolded him. “Why didn’t you give the rest of the water to the plants? What right have you to waste even a drop of water in this temple?”

The young student attained Zen in that instant. He changed his name to Tekisui, which means a drop of water.

Good one, right? If you’ve read it here before, congrats—you’ve been reading Keep Cool for over a year. Now, let’s transition out of the Buddhist Temple and onto the suburban lawn.

Inkjet sprinkling

A cul-de-sac. White picket fences. A sprawl of suburban lawns. In and of themselves, these images epitomize a society that isn’t concerned about resource efficiency. Suburbs aren’t energy efficient. They aren’t paragons of responsible land use. And they waste a lot of water.

Now, enter the ‘final boss’ of excess—the American lawn. Residential outdoor landscaping in the U.S. uses ~8B (!) gallons of water per day – more than showering and washing clothes combined.

Sure, not all of that is used for lawns, per se. But a lot of it is. And while California has enjoyed a blockbuster winter of rain, helping to replenish reservoirs, other areas in the U.S. are grappling with drought. The Great Salt Lake may soon be neither ‘Great’ nor even constitute a ‘Lake.’ The Colorado River could run dry. Water overuse, both in agriculture and in municipalities, doesn’t help.

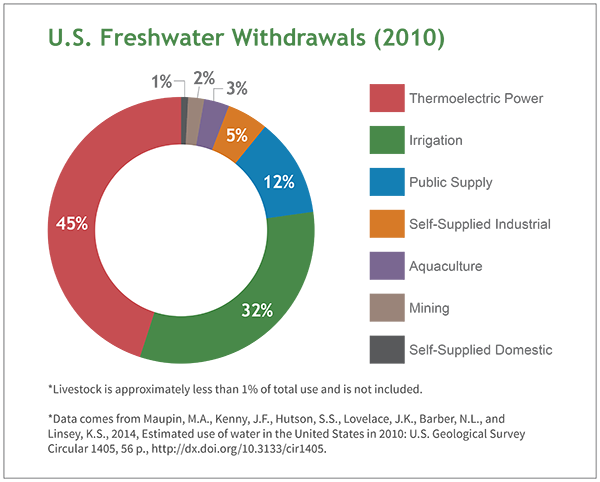

A bit dated, but this gives you a sense of just how ‘thirsty’ irrigation is (via the EPA)

Getting rid of lawns altogether, especially in desert climates, would be an excellent climate solution. But not everyone, e.g., golf course owners, is ready for that. To this end, there’s Irrigreen.

Irrigreen, which announced $15M in seed funding last week, wants to help save water in sprinkling. They use inkjet printing technology in robotic systems to use less water for the same level of irrigation.

I jammed with Shane Dyer, Irrigreen’s CEO, a few weeks back and asked him to break down inkjet printing for me, mainly to explain why it works for sprinkling. He noted that inkjet printing is a combination of hardware and software. Inside a printer, there are software systems that help the printer get more precise about where to place droplets of ink to make up a picture.

Similarly, Irrigreen wants to “print” water instead of spraying it. Said differently, their systems aim to spread water droplets efficiently in a uniform layer for more precise irrigation. This involves the hardware (the sprinkler head) and software to ingest data about the lawns on which sprinkler heads are deployed to understand where they need to and don’t need to spread water.

If you imagine the mechanical sprinkler systems you’re more familiar with, it’s easy to appreciate their inefficiencies. They ‘spray and pray.’ In the process, they over-irrigate, wasting water. There’s a bit of an irrigation industry standard “75/25” rule that encapsulates the inefficiencies of sprinkling: 75% of the lawn area is over-irrigated, so that 25% of the area isn’t under-irrigated. If that isn’t the most niche thing you learned today, kudos on being very in the weeds elsewhere.

How do you eliminate the 75/25 problem? Shane described each of Irrigreen’s robotic sprinkler heads as a “Bellagio fountain that traces the contours of your lawn.” Combining the enhanced calibration of the inkjet printing tech with the rotation of the sprinkler heads, which have 14 holes, all of which can change size, Irrigreen can cut the number of sprinkler heads needed for a residential lawn from ~30 to ~5. That simplifies installation and reduces piping and valving.

One of Irrigreen’s sprinkler heads (courtesy of the firm)

All in, a Fresno State Center for Irrigation Tech study found that Irrigreen’s systems can offer ~40% water savings compared to traditional sprinkler heads (controlling for soil moisture).

The (business) case for conservation

Even as folks start to care about things like saving water a bit more, venture-backed businesses (and businesses in general) are dead on arrival if they don’t also make money.

Fortunately, in Irrigreen’s case, saving money has always been part of the raison d’être. If you’re an inkjet printer inventor (like Irrigreen’s CTO, Gary Klinefelter, who has some 40+ inkjet printer patents), wasting printing fluid upsets you. Because ink is expensive!

Water is expensive now, too. It wasn’t always, which explains why Americans fell in love with lawns in the first place. But now water is more scarce, a ‘good’ catalyst for Irrigreen’s business. While having a technician come and ‘map’ your lawn and install their system requires an upfront investment, Irrigreen can offer payback periods shorter than those for rooftop solar by saving customers money on every monthly water bill. Specifically, they forecast payback periods as short as ~4-5 years when and where water rates are high and ~8 years when and where rates are low.

Nor is there reason to believe water won’t continue to get even more expensive. Some municipalities have already changed rate structures to escalate alongside water use: Water gets more expensive as you use more of it. I did press Shane on whether they’ll move beyond the residential market and lawns. Part of me wanted him to shout a resounding “YES!” I want to see these systems in industrial-scale agriculture, too—in the cornfields of Iowa and the soybean fields of Illinois.

Shane was pretty firm about staying focused on residential lawns to start. From his perspective, that will be one of the fastest areas to deploy. And municipal water tends to be the most expensive, meaning the highest cost savings to draft off of are in cities.

Part of my pressure on this front came from assuming that crops and orchards use far more water than lawn irrigation. Coming full circle, that might not be true. Some studies that have taken this question head-on concluded lawns might be the U.S.’s #1 irrigated ‘crop.’ By a wide margin, even. And a drop of water saved is a drop of water saved, regardless of where that happens or which crop it would have been in service of.

I would like to reiterate two primary insights.

We’ve hit this two weeks in a row now: Let’s repurpose more existing technology for new climate technology applications.

Here’s an entrepreneurial exercise. Make a list of a few dozen technologies from the past decades that cut costs or opened up new data streams. Stare at it. Go for a walk. Sit under a tree. Consider whether there’s a climate challenge to apply one of them to. Call me if you want to jam on it.

I’d also like to call back to the Zen koan we opened with.

Irrigreen’s tech might not seem like it will change the world or reverse climate change tomorrow. To which I ask you, which single technology will? (And I hear you, nuclear energy permabulls.)

It’d be a mistake to discount tech that offers incremental change, whether in energy efficiency or by saving water. In our pursuit of the big answers (whether climate solutions or enlightenment), we lose our way when we neglect ‘smaller’ wins (whether efficiency gains in sprinkling or mindfulness during daily chores). The latter is the path to the former.

Okay, that’s enough preaching. Plus, I almost forgot. Go to Irrigreen’s website if you or someone you know has a lawn! You can look up any house in the U.S. and visualize the potential layout (and start to calculate potential long-term savings) from their system.

Reply