- Keep Cool

- Posts

- Agricultural decarbonization runs through biology

Agricultural decarbonization runs through biology

Always has, likely always will

Hi there,

I just landed in Los Angeles for a brief trip to make my best friend’s birthday dinner. Because if you can, what the hell else is there to living? I’m also conscious there’s some seriously fucked up shit afoot, with LA as one epicenter for it, so I want to a) acknowledge that and b) send some healing energy to all in protest and / or in pain.

Anyway, let’s talk about agricultural decarbonization today, which I often lament is getting stepchild treatment compared to power sector, transportation, or even industrial decarbonization.

The newsletter in 50 words: The predominance of agricultural decarbonization and improved adaptation and resilience depends on biology and our (i.e., humans') more sophisticated and thoughtful working with what nature has already given us, much of which is marvelous beyond comprehension. Other “intermediate” interventions and inventions can help but prob won’t drive wholesale global change.

♡ If you find this work valuable, please support it here. You can do so for $1. The more of you who do, the more I can write! I put a lot of thought, time, and heart into it either way. ♡

⚡︎ P.S., want to highlight your company, brand, or project in these pages? Respond to these emails to get in touch. ⚡︎

OPINION / DATA DUMP

“Imagine a flashy spaceship lands in your backyard. The door opens and you are invited to investigate everything to see what you can learn. The technology is clearly millions of years beyond what we can make.

This is biology. That’s why it fascinates me so much. Life is billions of years old technology…”

The above is a perfect encapsulation of the gist of this article, in which I’ll argue that the predominance of agricultural decarbonization and improved adaptation and resilience depends on biology and humans working with it more sophisticatedly. Other “intermediate” interventions and inventions can help but prob won’t drive wholesale global change. This has long been the case; while the main focus historically has been on improving crop yields and resilience to pests, heat, and drought and, in animal husbandry, selecting breeding for docility, meat, and milk, these are all practices equally pertinent to keeping emissions down, even if total global greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are still on the rise, or at least close to all time highs.

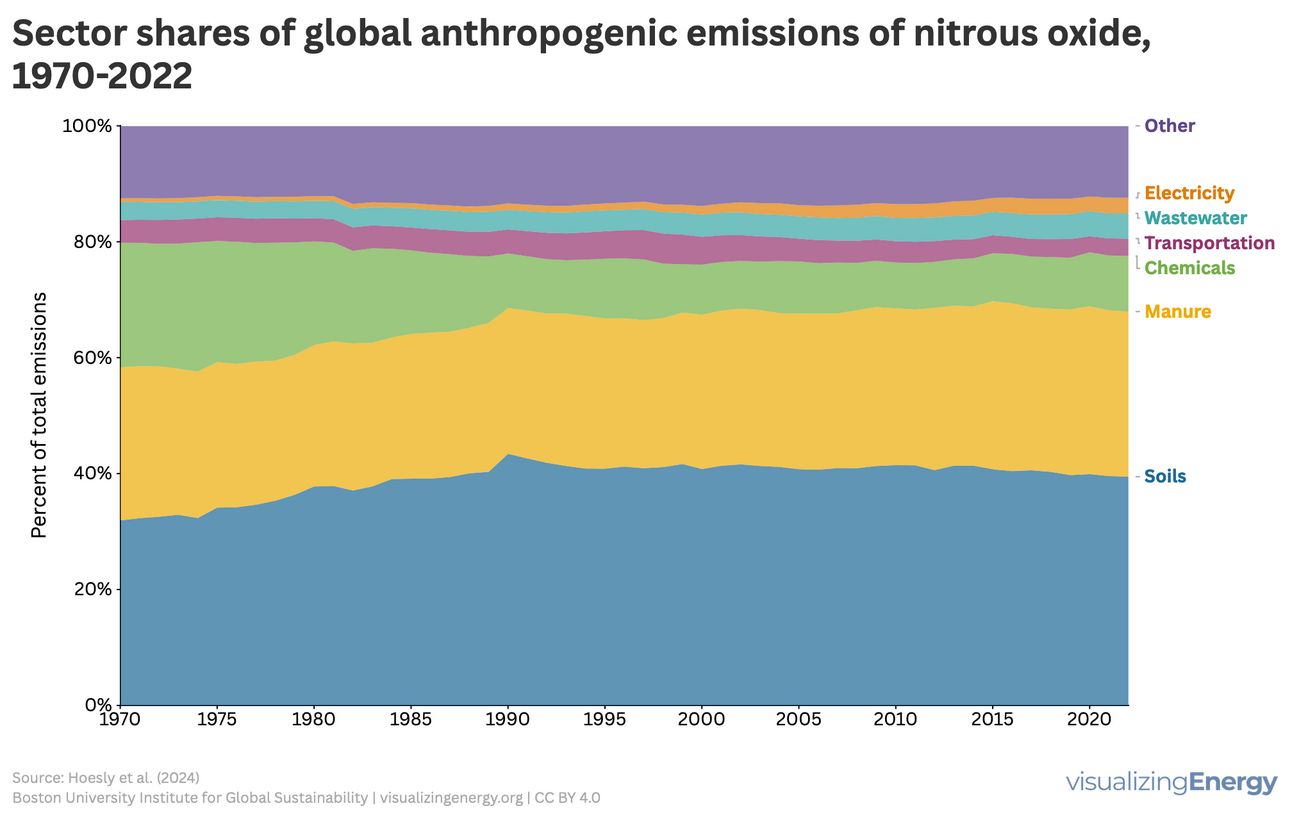

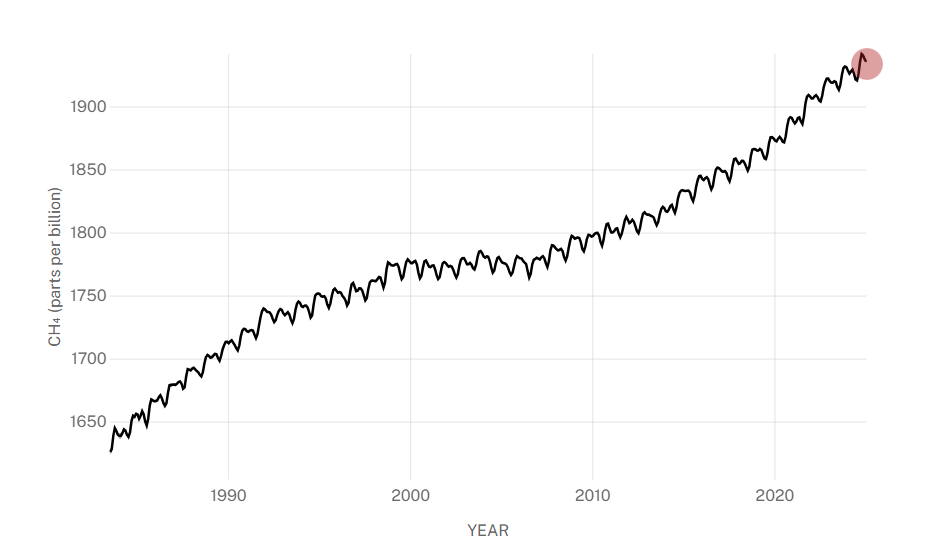

Nitrous oxide emissions, largely a product of agricultural operations, remain on the rise, in particular to continuing proliferating synthetic fertilizer use and overapplication

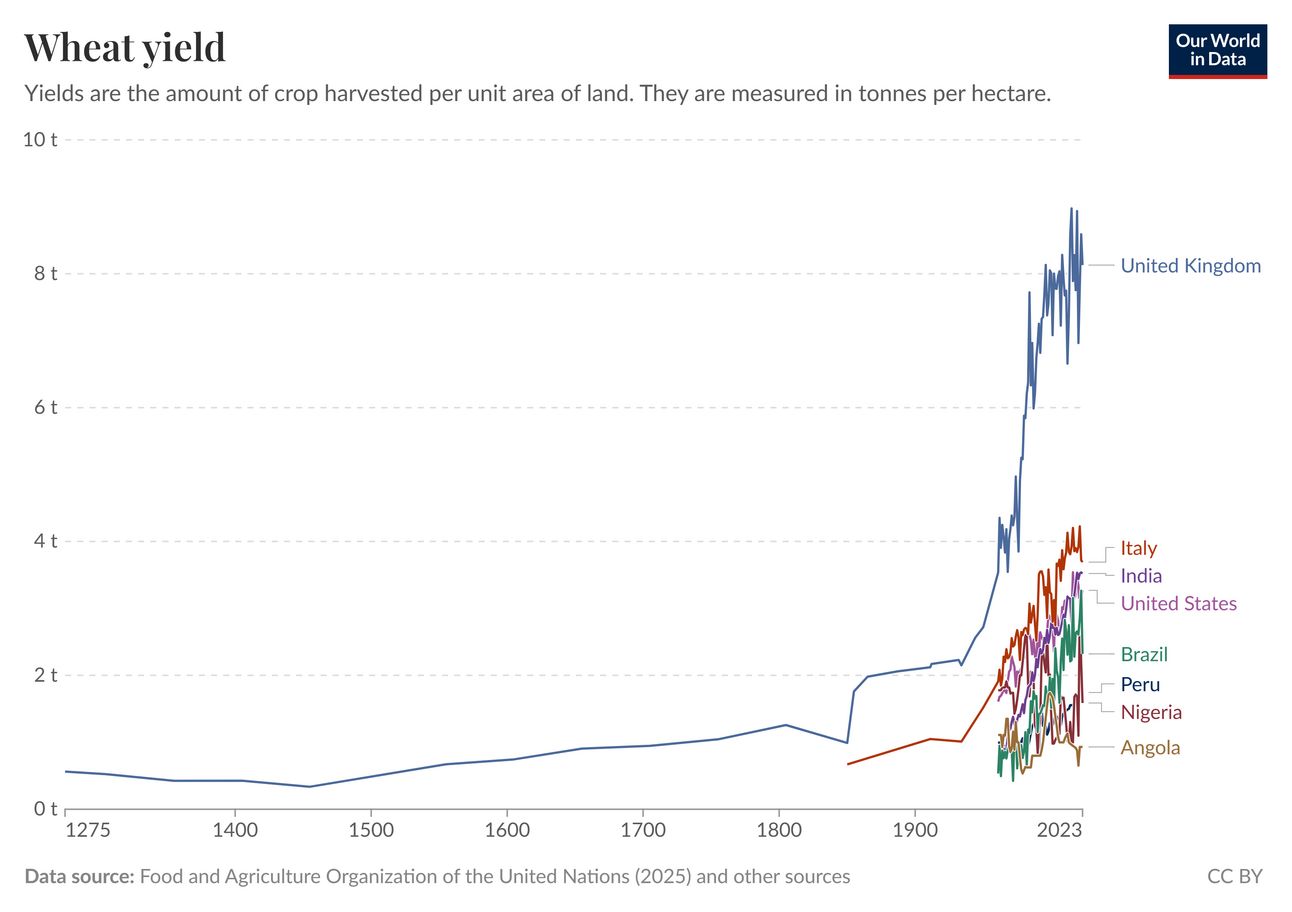

The fact that emissions are still rising is a consequence of population growth, not a lack of improvements in efficiency in agricultural outcomes, which are driven in large part by the elegance of “machines” designed by nature and natural selection, and as gently nudged by increasing human intervention. One need only take a cursory look at trends in staple crop yields over long time horizons (or even over not-that-long ones) to get the idea:

Might as well go a level or two deeper than a cursory look, however, as long as we’re here.

The biological “nudge” goes anthropogenic

In news that doesn’t on its surface seem to immediately have much to do with decarbonization, sustainability, adaptation, or resilience, a company called Nucleus Genome recently announced a software service whereby paying customers can scan and select for desired traits in embryos for their prospective offspring, notably including traits beyond health and inherited diseases, including much more speculative ones like IQ.

That may strike you as a dystopian step towards eugenics. Not an unreasonable reaction, albeit this is also not an ethical or philosophical bog I will wade into today in much depth. Plenty of unabashed eugenicist pros were excited about the news. That said, eugenics, at least when narrowly confined to focus on, say, the elimination of insidious, genetically inherited disease, needn’t inherently spell racism. Embryonic shopping was probably always an inevitability (and embryonic elitism is likely an invariability as well, given the implied meritocracy of looks, intellect, wit, and whatever else you find attractive are irresistible levers for our hardwiring to ignore once available). After all, there’s already a Chinese scientist who went to prison for successfully genetically engineering babies.

I digress, suffice it to say that while inventing new technologies is not something humans as a species struggle with, evaluating whether and when the potential second, third, quartiary, and so on externalities of their proliferation outweigh the merits of commercialization is not something we’re necessarily particularly hardwired for.

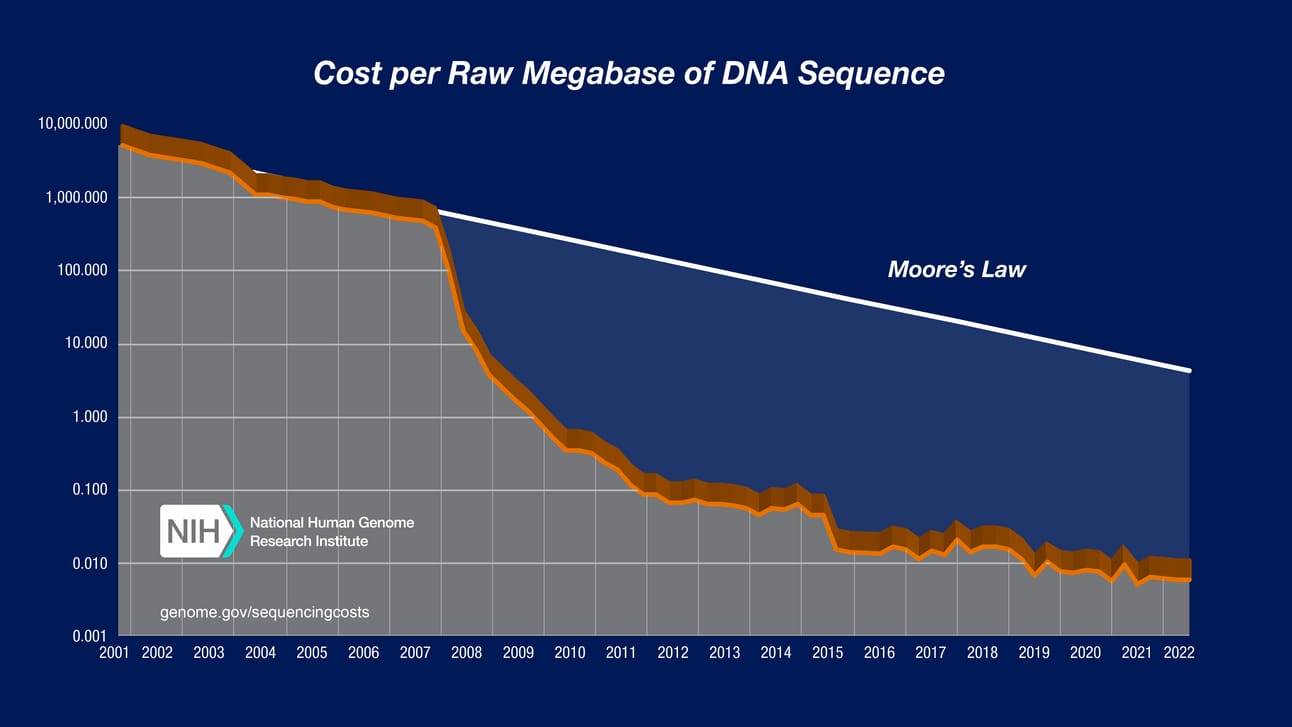

For our purposes today, and without my making any claims about how well this new company will do or how well it’s technology even works, the news is a testament to how far technologies like genetic sequencing and modification, genomics in general, computational biology, and all the hardware that make these things possible, better, and cheaper, have come. Illumina, the gold standard in hardware for DNA and genetic sequencing, is a ~$14B company for a reason, and Jennifer Doudna and colleagues discovered CRISPR well over a decade ago, back in 2012.

As far as present-day applications thereof are concerned, there’s new news by the week. This week, there are papers out about Cat1, a bacterial protein scientists recently discovered that stops viruses by breaking down NAD+, a molecule cells need to survive. When activated, Cat1 forms spiral structures that trap NAD+, essentially starving infected cells, preventing them from replicating viruses. Unlike typical CRISPR systems, which sort of ‘surgically cut’ viral DNA, Cat1 shuts down cell metabolism entirely. The protein often functions alone, illustrating that bacteria have an additional antiviral strategy beyond the DNA-targeting CRISPR mechanisms people were familiar with.

Hence, it’s this biologically-engineered machine’s opinion that nature has always and long will make more marvelous “machines” than man. Sam Altman’s latest, blowsy AI think piece be damned. Akin to the quote I opened on, this idea isn’t my own. It was first gifted to me by another marvelously biologically-engineered machine, Eben Bayer, when he casually remarked to me, five years ago in a conversation otherwise about AI and such, that “the chicken is also a highly advanced technology.”

Now, here’s why this is highly pertinent to agriculture, perhaps most of all sectors, at least when concerned with decarbonization.

Agricultural decarbonization all runs through biology

For another example, take, say, the outstanding fact that photosynthetic organisms, without moving much physically, constructing anything save for their own bodies, moving much mass in general or moving themselves dramatically, let alone leveraging the Rankine cycle, produce and make use of ~8x more energy than human society uses. Similarly, as I wrote about in this piece about why biodiversity is an economic necessity, industries like pharmaceuticals are deeply dependent on studying and then using the most inventive and elegant solutions evolution has already cooked up.

Ozempic? GLP-1s in general? The rise of Novo Nordisk stock ($nvo stock ticker!)? Inspired directly by venom in Gila Monsters’ spit that regulates feelings of satiety.

🎶🎶 queues up the song “Gila” by King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard 🎶🎶

Why do I think this matters most for agricultural decarbonization? Because manipulation of existing biology, as I opened with, has long been the name of the game for agriculture advancement. It basically is agriculture. Selective breeding, while not always dramatically high-tech, at least historically, has similarly been the preferred solution for innovation in animal husbandry since that has been a thing. Similarly, as much as the Office of Management and Budget may think a minuscule amount of funding for “legume systems research” is silly, crop rotation and the nitrogen fixing properties of beans are a more civilization-defining practice than nuclear fission is so far.

a recent sardonic government tweet that got ratiod to death

The same could be said of many other more recent manipulations and amendments built on top of existing biologies and made possible by getting better at working with biology directly. One I often highlight is that rust resistance genes “engineered” by Norman Borlaug that were so successful they now appear in 80% of global wheat varieties.

Echoes of the same conclusion ripple throughout animal husbandry, which effectively began with selective breeding, some level of which was necessary to induce enough docility in animals to keep them around and make them willing and symbiotic companions to humans and our settlements. That’s true whether you look at dogs, horses, or cows. As written in a wonderful book review in The New York Review of Books recently, “The Rise and Fall of Warhorses” by Wendy Doniger:

“Over several centuries of breeding on the steppes, horses not only gained more muscle and endurance but “developed more warlike instincts, losing some of the fearfulness of their hunted ancestors.” Bred and selected for courage, they could “jump over obstacles, pass through flames and explosions, or carry on when wounded…. [They overcame] fears of dragging an encumbrance, loud noises, and water obstacles.” The extreme movements in that most rarefied of all forms of horsemanship, dressage—the levade, in which the horse raises and draws in its forelegs, standing balanced on its bent hind legs; the courbette, a jump forward at the levade; and the capriole, in which the horse jumps straight upward, with its forelegs drawn in, kicking back—were originally developed as a series of exercises to train warhorses to kick and trample human and equine enemies in battle.

These great changes in the form and behavior of horses were achieved through single-minded breeding, the method by which various political groups made horses what they wanted them to be.”

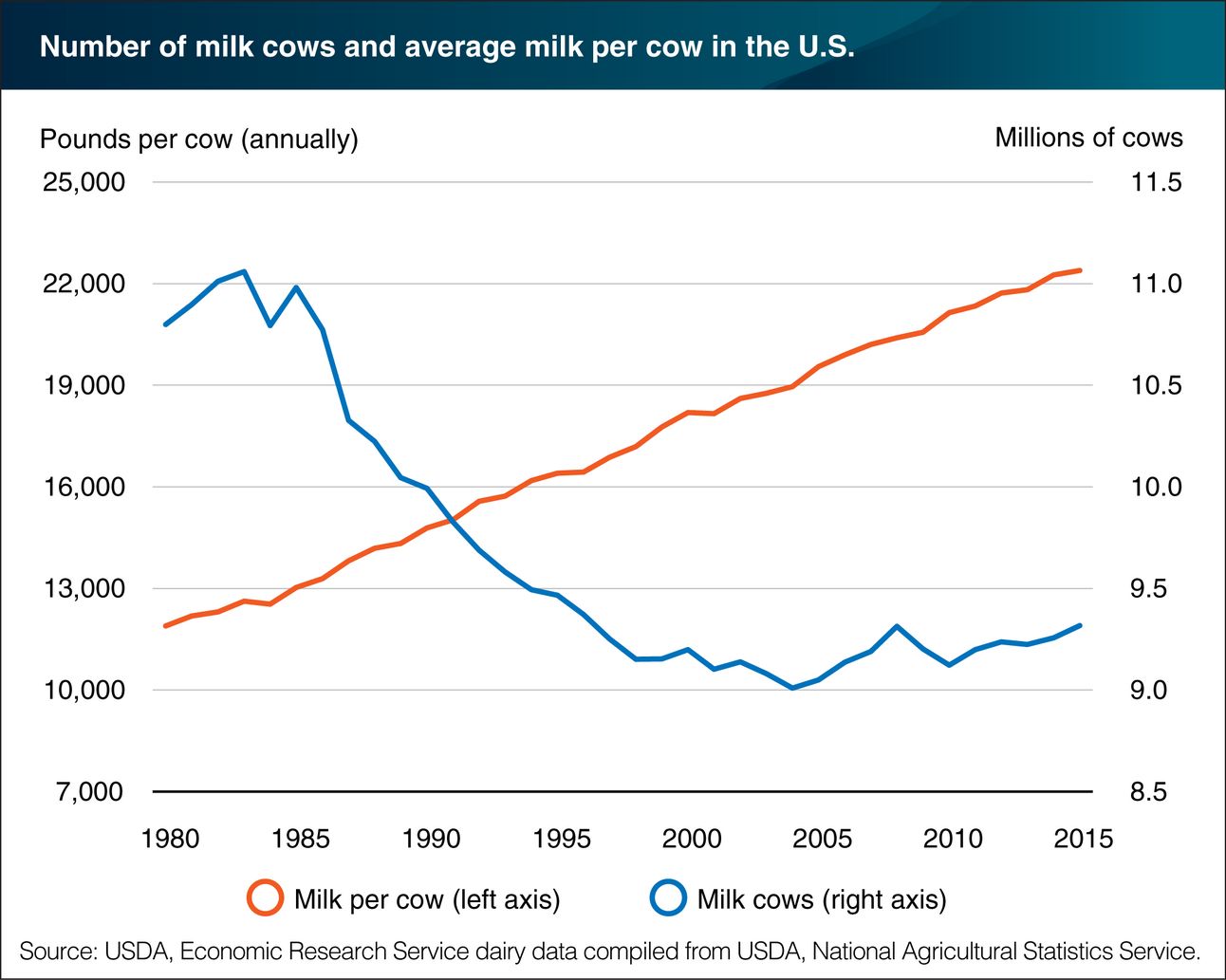

Cows are a great example of an area where selective breeding, admittedly increasingly aided by more sophisticated, non-biological technology, has done more for the sustainability of agriculture than much else has. While it’s often true that making machines more efficient doesn’t mean society uses fewer of them (think semiconductors, which are unimaginably more efficient today than decades ago, but, as a consequence, get packed tighter and tighter onto more and more smaller circuits and transistors in more and more devices, resulting in more, not less of them), there are far fewer cows per capita on Earth today than there were in 1960.

In 1960, there weren’t that many fewer cattle on Earth than today.

The human population, meanwhile, was less than half its current size.

In large part, that’s because the cow, on average, is much more “efficient” at producing meat and milk today. Dramatically so in developed economies.

If we were still trying to feed 8 billion people on the average 1960 cow, or with average 1960 crop yields and crop resilience, we’d be in deep trouble and the population likely wouldn’t be what it is. Sans thoughtful manipulation of existing biology, feeding the world would otherwise require razing almost all the world’s forested land, as opposed to a substantial whack of it. And we’d probably be at 3,000+ ppb (admittedly unscientif guess) methane in the atmosphere, or more, versus the already staggering 2,000 ppb.

Atmospheric methane concentrations are up 20%+ in ~40 years. if cow “efficiency” weren’t improving, we’d be in much more trouble considering how rapidly methane drives warming

What am I driving at here? I’ve sort of said it three times, as I often do, but here goes one more time: As far as agricultural decarbonization is concerned, I’m not massively bullish on other intermediate interventions (i.e. ones not immediately dealing with subtly, or even dramatically manipulating existing biology). Examples I think can be helpful but not revolutionary include, say, feed additives that purportedly reduce methane emissions in ruminant livestock and maybe also improve their feed conversion efficiency, both of which are still largely speculative assertions at this point that require a lot more bearing out. I will say if there are feed additives or vaccines that are fundamentally more enzyme-redefining and don’t require routine application, that’s different. Rather, straight up selective breeding for lower methane traits, especially considering how fast cattle generations can turn over, excites me more (and I recently invested in a company working in that area). Similarly, things like modular hardware that makes fertilizers onsite from sun and air to reduce emissions-intensive synthetic fertilizer production are cool. But I don’t see them taking over the world.

That’s not to shit on those ideas or discourage their development and investment in them. By all means, go for it and try. Rather, it’s just to say what’s improved agriculture for 10,000+ years, from a Lindy perspective, is likely the best bet for the next decades. Especially aided by advances in AI & ML; as reticent as I am to loop those in cheaply; they already have helped for some time, well before the current AI mania (see, for e.g., genetic sequencing cost.)

Plus, as the Overton window shifts such that the technology goes through “application leap” to humans as well, even more capital will pour into it. I’m not sure the long-term results of extensive use for human applications will be entirely savory, let alone satisfactory, as the complexity of what makes humans wholly healthy, happy, and “hot” is probably a cocktail whose recipe will elude us for some time, if not forever. But, as far as agriculture, livestock, greenhouse gas emissions from them, and comprehensive sustainability, resilience, and adaptation are concerned, the existing approach probably remains best. LMK if you disagree.

WORTH A LISTEN

Here’s a panel I helped model on distributed energy technologies at the DER Task Force’s outstanding annual event, DERVOS, last year. Tix on sale for this year too here.

Stay safe out there and stand up to some wrongdoing in your community as you can,

Nick

Reply